STOKE ST MARY AND DISTRICT HISTORY GROUP

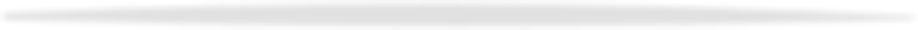

ROUTE FOR THE “BRISTOL AND ENGLISH CHANNEL JUNCTION CANAL”

PROPOSED BY JAMES GREEN

It started at Beer, on the English Channel

There would have been a pier built at sea level.

Goods would have been unloaded from the merchant ships, transported up to the canal wharf, some 70ft above sea level, and loaded into “tub boats” rather than barges.

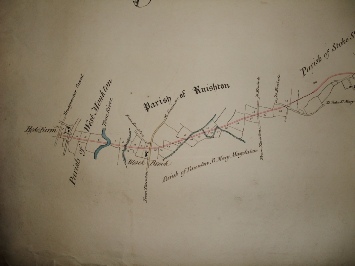

Between Beer and Seaton there would have been a quarter of a mile tunnel. From Seaton, the canal would have run north, approximately following the River Axe, as far as Yarty Bridge, where there was to have been a 61ft “incline”. Another “incline” of 129 ft would be at Titherleigh, then a level section or “pound” of some 13 miles at the summit at Chard.

An Incline at Windmill Hill up the escarpment, and another of 190 feet at Stoke St Mary back down. An aquaduct would have taken the canal over the Tone, and it would have joined the Taunton to Bridgwater canal at Hyde Farm.

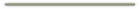

The last part of the route from Windmill Hill, past West Hatch and along the hill just above Stoke St Mary. An “incline” down the hill, and then on to Hyde Farm.

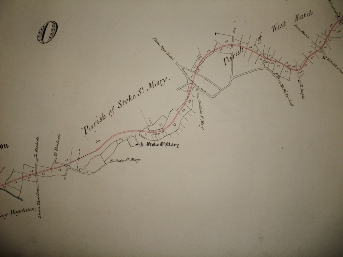

James Green’s actual drawing of the route of his canal above Stoke St Mary

Unfortunately on James Green’s map there are no buildings included, other than the church.

But one can suppose that the canal would have gone somewhere between Stoke House at the bottom of Stoke Hill and Stoke Castle at the top.

JAMES GREEN’S CANAL

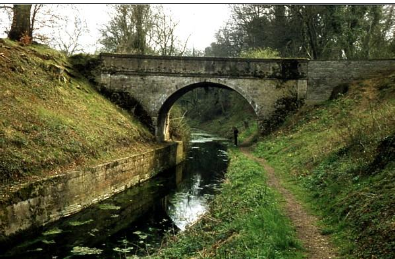

It would probably have been similar in size to his Bude Canal. About 23 feet wide and 3 feet deep.

A towpath at the side and possibly steep slopes..

Green estimated the cost of construction at around £120,000 including the building of the pier at Beer.

Sadly though a brilliant engineer and surveyor he was not so good at estimating costs, so it might well have cost quite a bit more.

The draw-

Cargoes would have to be off loaded onto the small tub boats at either end, and then, once they reached the other channel, reloaded onto the large merchant ships for onward transmission. Something Sir John Rennie had hoped to avoid with a large ship canal.

The tub boat was rectangular in plan, about 19 feet 9 inches long by 6 feet 2 inches wide by 3 feet deep, made of wrought-

An empty boat drew about 3 inches of water and on loading it drew about 4 inches per ton up to a maximum of 5 tons. The maximum draught was 2 feet but on the Duke of Sutherland's Canal this was reduced to a draught of 1 foot 3 inches with a maximum load of 3 tons.

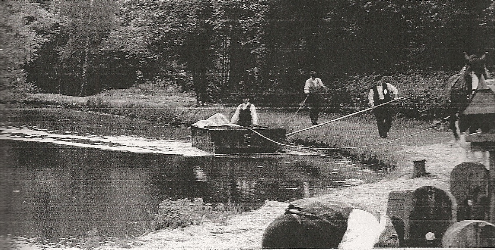

Towpaths were provided and tub boats were hauled by horses in trains of 6 boats together .

They were steered by a man walking along the towpath who kept the leading boat in the middle of the canal by pushing against it with a long pole.

INCLINED PLANES

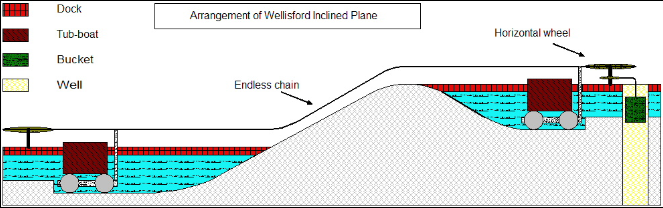

Basically an Inclined Plane was a steep, smooth slope with rails running up and down the slope and a winch or drum with a cable at the top.

There would be four inclines, taking the canal to over 260 ft above sea-

James Green argued that with his inclines great heights could be reached in a relatively short length and although the Stoke St Mary incline was not the highest he had designed Hobbacut Down, on the Bude Canal was 225 ft, it would be testing enough for the unsophisticated winding machinery of the time.

Compared to the customary design of canals, where pound locks were used to raise or lower the water levels over any gradients, these long inclines were audacious proposals, derived from the principles of the pit inclines but where horse power was replaced by water.

On the Bude canal the boats were fitted with wheels, which engaged with rails on arrival at the top or bottom of the inclined plane.

Other wise the tub boats were floated onto a wheeled cradle and pulled up the incline.

On a double track incline the weight of the descending boat and cradle could help to draw up another loaded boat. If it was found that the weight of the descending boat/cradle was not sufficient an engine had to be added..

The majority of Inclined Planes that were built were the double track variety.

Later on again, the tub boats were floated into wheeled caissons [“metal bath-

There was a short track [with a different gauge] at the top of the incline that let down into the top canal. The caissons had two different sets of wheels. Large wheels at the back and small in the front for going up the main incline and the other set had the reverse order for going down the short top track. This ensured that the tub boats remained relatively horizontal.

Sadly for Stoke St Mary, although there was a great deal of enthusiasm for Green’s proposal and they were going to go ahead with the plan, another proposal was put forward and as this was for another Ship Canal, Green’’s proposal for a Tub Boat Canal was withdrawn.

Stoke St Mary never got her canal

The new proposal , put forward by Thomas Telford, was for a huge 124ft wide, 23ft deep ship canal, 41 miles long with up to 60 locks. This canal would not have passed Stoke St Mary but it would have gone down past Lime Kiln Cottage, Ashe Farm and the Nags Head. A possible alterntive route might have taken it past Thurlbear.

This too never made it pass the planning stage. The investors were not forthcoming, and with an estimated cost of one and three quarter million pounds, one can see why. And before long they were past the age of the canal and into the age of the railway and the steam ship.

So the Bristol and English Channel Company never managed to build a canal.

For more information of Somerset canals press HERE