STOKE ST MARY AND DISTRICT HISTORY GROUP

STOKE ST MARY LIME KILN

|

FIELD NO |

FIELD NAME |

OCCUPIER |

CULTIVATION |

OWNER |

|

|

|

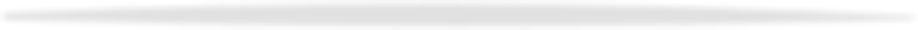

243 |

Southfield |

Murless, Amelia |

Meadow |

Murless, Amelia |

|

|

|

244 |

Marshall's Ground |

Murless, Amelia |

Pasture |

Murless, Amelia |

|

|

|

245 |

Quarry Close |

Dawe, Charles |

Arable |

Prior, Edward |

|

|

|

246 |

Sheppard's Orchard |

Murless, Amelia |

Orchard |

Murless, Amelia |

|

|

|

306 |

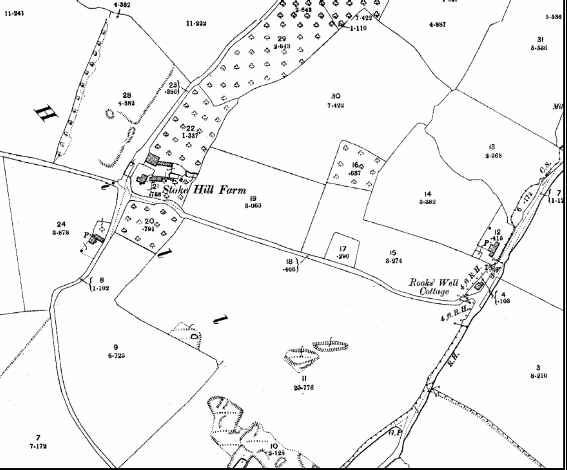

Goose Acre |

Murless, Amelia |

Meadow |

Murless, Amelia |

Dwelling house |

Garden, stables |

|

307 |

Nine Acres Orchard |

Dawe, Charles |

Orchard |

Prior, Edward |

|

|

|

308 |

Rook's Well Mead |

Dawe, Charles |

Meadow |

Prior, Edward |

|

|

|

309 |

Half Acre Orchard |

Murless, Amelia |

Orchard |

Murless, Amelia |

|

|

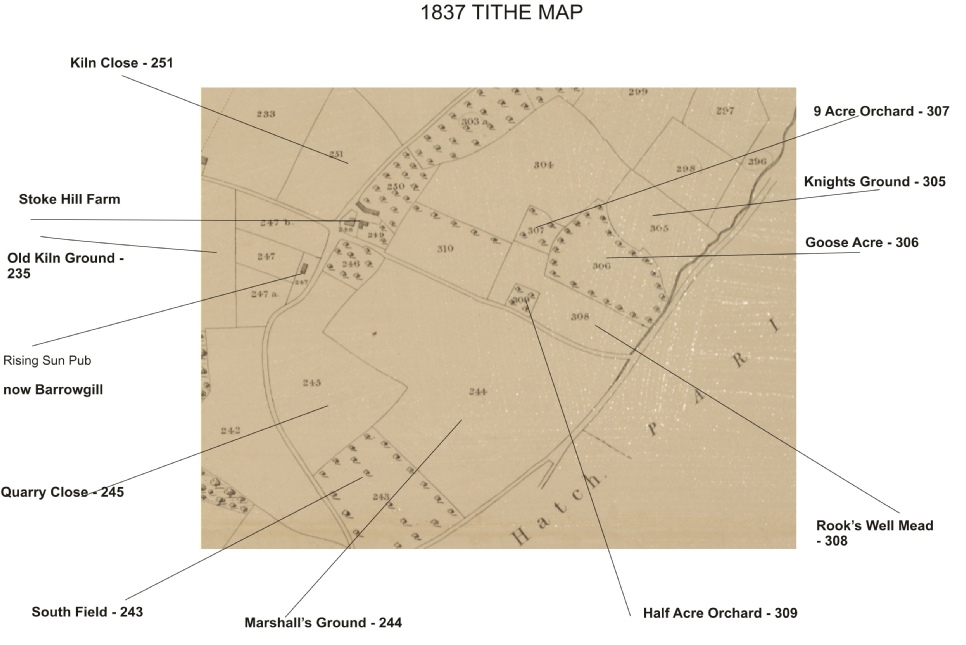

According to the 1837 Tithe Map the land around the lime kiln was owned by Amelia Murless and Edward Prior. The nine acre orchard and Rook’s Well mead were farmed by Charles Dawe.

The fields and lime kilns were then owned by Samuel Stodgell, owner of Stoke Castle. He is recorded as providing lime to the Church in Stoke St Mary when there was building work being done. Samuel Stodgell died in 1872 and left his estate to his sister, married to Samuel Tapp. Their daughter was married to Wareham Hull and so some of the land passed into his hands. Though it rather looks as if the lime kiln then was in Marshalls Field. The land was bought by Aaron Small from Stoke St Mary, father of George Small.

Listed Buildings in Stoke St Mary -

Pair of limekilns. Dated 1906. For G Small and Son. Blue lias squared and coursed. Plan: pair of limekilns set into hillside with small square vent between just above ground level. Semi-

Lime Kiln Cottage

Lime Kiln Cottage is of Blue Lias stone and rendered elevations under tiled roofs and comes to the open market for the first time in almost 100 years having been in the same family occupation in the intervening years. The property probably dates back around 250 years and retains many of the original features including inglenook fireplaces and exposed timbers.

NOTES ON A CONVERSATION WITH CECIL AND MARY CLARK OF LIMEKILN COTTAGE, STOKE ST MARY, RELATING TO THOMAS BURT, LIME BURNER, MRS CLARK'S FATHER, 13 JULY 1982

The double kilns beside Lime Kiln Cottage, Stoke Hill, bear a stone with the date 1906 and the initials “G.S.” those of George Small, builder and Limeburner of Furze Cottage, Stoke St Mary. Thomas Burt, born at Rook’s Well Cottage, Thornfalcon, in about 1890 (he died in 1963, aged about 73), was subsequently employed by Small’s to run the kilns, moving to Lime Kiln Cottage when his daughter, Mrs Mary Clarke, was six years old. He continued to operate the kilns until 1939, and apparently gave them up when the quarry in the field behind, Rooks Well Mead, was worked out.

The lias strata around Stoke, West Hatch and Thurlbear runs diagonally downwards in three layers composed of blue lias, “rubbish” stone and “white rock”, the last being the most durable and the preferred building material. Both blue lias and white rock were used for burning into lime.

In the old days small kilns might be built wherever there was a lias outcrop and operated until the strata went down too deep to be easily worked. Stoke, West Hatch and Thurlbear were much associated with the trade though Curry mallet had its own kilns. The kilns of 1906 were of a larger scale than most others locally and survived the longest.

The working day at the kilns was from 7 am to 5 pm and payment was made by the yard (presumably of stone quarried). Five or six men regularly worked under Tom Burt notably the members of the Morse, Wadham and Hector families. Frankie Wadham would walk to the kilns from his home near Winterwell, Thurlbear and is remembered arriving with his bread and cheese tied up in a red handkerchief carried over his shoulder at the end of the stick. They would cook bloaters by the heat of the kiln and bake potatoes as a treat for the children. There was always tea to be drunk, though cider was what they liked best. The kilns were a favourite stopping place for tramps who would spend the night by their warmth.

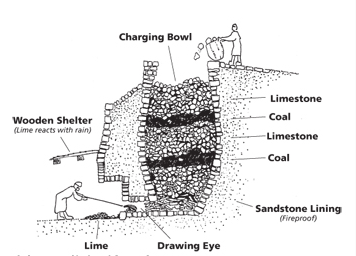

The stone having been quarried, it was brought up in wheelbarrows along a network of planks and piled near the top the kilns on the eastern side of Rooks Well Mead, there it would be broken into pieces ready for burning. The burning process itself took place in a shaft lined with fire bricks which was built into the back of the kiln structure and occupied its full height. Alternate layers of small coal called Culm (pronounced “culum” by the Clarkes), stone, dirt and culm, each about five or 6 inches in depth, was shovelled into the shaft and once the burning had begun regular replenishing meant that the fire never entirely went out. The culm was wetted with well-

The stone having been quarried, it was brought up in wheelbarrows along a network of planks and piled near the top the kilns on the eastern side of Rooks Well Mead, there it would be broken into pieces ready for burning. The burning process itself took place in a shaft lined with fire bricks which was built into the back of the kiln structure and occupied its full height. Alternate layers of small coal called Culm (pronounced “culum” by the Clarkes), stone, dirt and culm, each about five or 6 inches in depth, was shovelled into the shaft and once the burning had begun regular replenishing meant that the fire never entirely went out. The culm was wetted with well-

By 6.30 in the morning the farmers would already have their carts lined up in the road outside Limekiln cottage anxious to take a load of lime while the day’s supply lasted. They used it mostly on the land as a fertiliser and as a means of keeping the fields clean but it was also used for making mortar and for whitewashing. They came from all the villages around and from as far afield as Ilminster and Bridgwater and one farmer from North Petherton is specially remembered for his horses splendidly turned out with horse brasses. The carts would be backed up to a platform near the mouth of the kilns and loaded with lime from barrows. A heaped barrow was reckoned as a hogshead, the measure by which the lime was sold though if a farmer was so thoughtful as to bring some cider he could expect to be given a little more line for his money. Built into the wall in the mouth of each limekiln was a safe where Tom Burt kept his ledgers and the money was taken.

When the day's work was over, the fire would be damped down by placing a wooden flap over the opening at the base of the shaft and making it air-